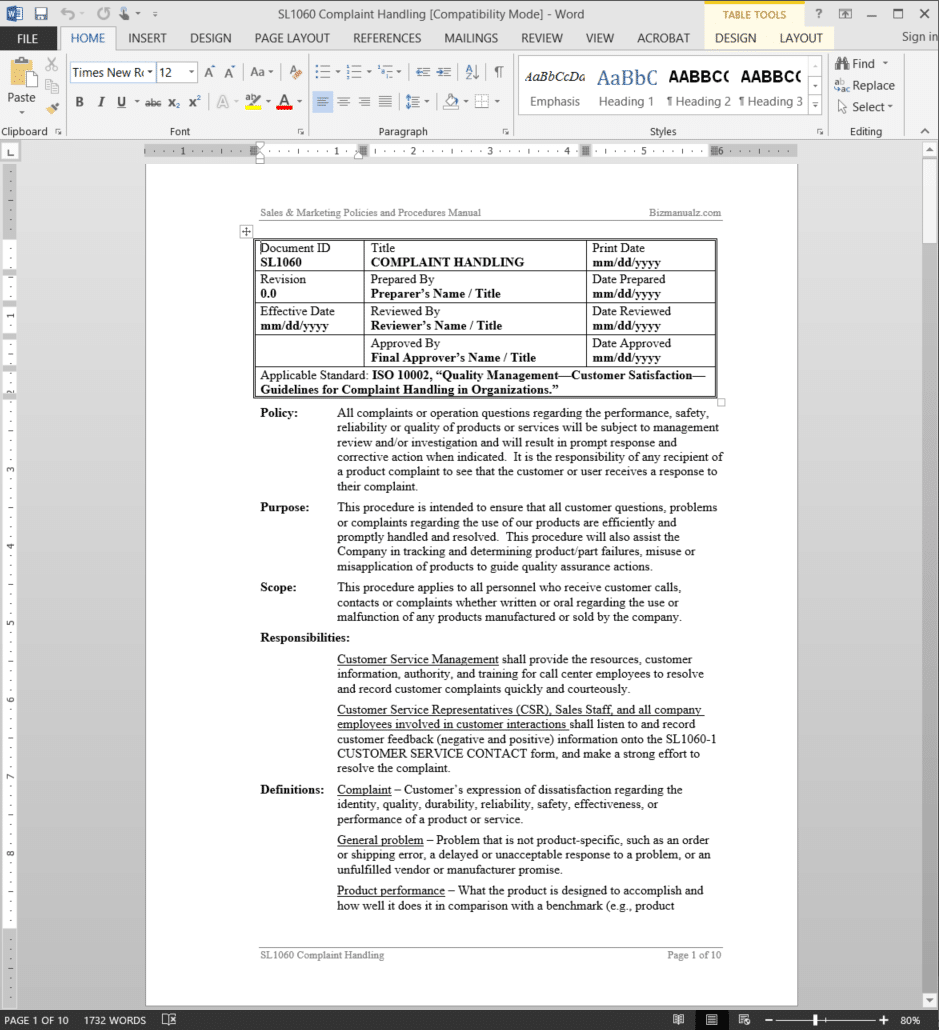

Complaint Handling Procedure

Complaint Handling Procedure

The Complaint Handling Procedure ensures that all customer questions, problems or complaints regarding the use of our products are efficiently and promptly handled and resolved. It will also assist the company in tracking and determining product/part failures, misuse or misapplication of products to guide quality assurance actions.

All complaints or operation questions regarding the performance, safety, reliability or quality of products or services will be subject to management review and/or investigation and will result in prompt response and corrective action when indicated. It is the responsibility of any recipient of a product complaint to see that the customer or user receives a response to their complaint.

The Complaint Handling Procedure applies to all personnel who receive customer calls, contacts or complaints whether written or oral regarding the use or malfunction of any products manufactured or sold by the company. (10 pages, 1,732 words)

Complaint Handling Responsibilities:

Customer Service Management should provide the resources, customer information, authority, and training for call center employees to resolve and record customer complaints quickly and courteously.

Customer Service Representatives (CSR), Sales Staff, and all company employees involved in customer interactions should listen to and record customer feedback (negative and positive) information onto the SL1060-1 CUSTOMER SERVICE CONTACT form, and make a strong effort to resolve the complaint.

Complaint Handling Definitions:

Complaint – Customer’s expression of dissatisfaction regarding the identity, quality, durability, reliability, safety, effectiveness, or performance of a product or service.

General problem – Problem that is not product-specific, such as an order or shipping error, a delayed or unacceptable response to a problem, or an unfulfilled vendor or manufacturer promise.

Product performance – What the product is designed to accomplish and how well it does it in comparison with a benchmark (e.g., product specifications, a predetermined standard, a competing product, and/or user expectations).

Product safety – Condition of being safe from injury or loss due to use of the product; condition deliberately designed into a device to prevent injury or loss due to its inadvertent or hazardous operation.

Product reliability – Dependability; extent to which the product yields consistent results over time; product’s failure rate or need for service meets or exceeds user expectations.

Complaint Handling Procedure Activities

Complaint Handling Procedure Activities

- Receiving a Contact/Complaint from a Customer

- Troubleshooting/Problem Diagnosis

- Repairs and/or Replacements

- Trend Analysis

Complaint Handling Procedure References

- SL1090 SERVICE SATISFACTION

- SL1070 POST-SALE FOLLOW-UP

- ISO 10002:2004, Quality Management-Customer Satisfaction-Guidelines for Complaints Handling in Organizations.

Complaint Handling Procedure Forms

Go Beyond Customer Surveys and Complaints

These methods can provide useful information, but they also have serious limitations when it comes to capturing what customers really want. It can take a lot of effort to truly understand the meaning behind survey responses and complaints.

Being proactive in hearing, and most importantly, understanding the voice of the customer means more than just having customers complete surveys and then compile results. It can take more than statistics to really understand what customers want or mean.

Let’s review a couple of well-known examples of how taking time to understand the meaning behind complaints and feedback can lead to simple solutions that have a dramatic impact on customer satisfaction.

Are Expected Complaints Acceptable?

Most of us have been to large amusement parks and had to wait in long lines for rides. One well-known amusement park carefully monitored customer feedback, and the most frequent complaint was the long wait for rides. This complaint was ignored for a long time, however, because it was expected that people would complain about lines and because there didn’t seem to be a reasonable solution. Building duplicate rides to reduce waiting times wasn’t feasible. Making the ride operation more efficient had limitations and a minimal impact on waiting times.

Eventually, however, a more in-depth investigation into this common complaint was conducted. It involved asking follow-up questions in order to understand what people didn’t like about the wait. After all, if people expect to wait in line for rides, why would they complain about it? So as interviewers tried to determine why people complained about waiting in line, they discovered it wasn’t so much the wait that people didn’t like. It seemed that people were most bothered by having no idea how long they would have to wait when they joined the queue. They did not know if it would take 30 minutes or two hours. Apparently, it was the lack of information about the wait that they didn’t like.

When the amusement park added signs along the queue informing people how long they would have to wait, complaints about waiting in line dropped significantly. It seems that by having that information, people felt less helpless about the wait, plus they could decide when they arrived at the end of the line if they wanted to wait or go do something else. Now these waiting time signs are common at most large amusements parks.

Having this information also allowed the parks to “under-promise and over-deliver” as they made extremely conservative estimates about the wait. Having to wait 45 minutes instead of an hour (as the sign indicated) exceeded the customer’s expectations.

What Are Customers Really Complaining About?

In another case that involves looking for meaning behind the voice of the customer, a developer built a tall skyscraper. As the project was completed and tenants were moving in, the developer collected feedback from the tenants about the building before closing out the contracts with the various contractors. He wanted to make sure everything was done properly to satisfactorily meet the tenants’ needs.

After completing an extensive survey of tenants, he was surprised to find one of the most common complaints was slow elevators. The developer in turn complained to the elevator company. The elevator company provided the developer with timing statistics to demonstrate that the elevators weren’t really slower than other elevators, but the developer wasn’t convinced. Eventually the elevator company made some minor adjustments that increased the elevator speed a small degree.

A follow-up survey, however, demonstrated no change. People still complained about the slow elevators. The developer began to insist on major, expensive upgrades to the elevator system to make them operate significantly faster. The elevator company lobbied for some time to study the problem. They knew their elevators didn’t operate any more slowly than elevators in other buildings, so there must be something else involved.

Observing Customers in Action Provides Important Information

The elevator company hired a behavioral scientist to study the problem. The behavioral scientist spent a few days at the building riding the elevators and observing people. The conclusion reached after carefully observing body language, facial expressions, and other behavior was that people were very bored when waiting for and riding on the elevators. The tenants didn’t seem to realize that they were bored; they just knew it seemed to take forever for elevators to arrive and to deliver them to their desired floor. So they complained that the elevators were slow.

Instead of spending a large sum of money making the elevators go faster, the elevator company spent a little money installing mirrors inside the elevators, and the developer spent a little money decorating the bare and too-generic lobby area around the elevator bank with paintings, plants, and furniture. These minor changes kept people more occupied while waiting for and riding the elevators, thus the slow elevator complaints dropped drastically.

Apparently the behavioral scientist was right. There was no problem with the elevator speed. The problem was that the lobby and the elevators were boring, and people were bored when using them. Being bored made the time drag, thus the “too slow” complaint.

Not all customer feedback and complaints have hidden meanings. But they might. If you take all your customer feedback at face value you could be missing opportunities for breakthrough improvement, or you could invest time and money to fix problems that don’t really exist.

Sometimes you have to find proactive and inventive methods to find out how customers really feel about your product or service. That might be creating opportunities to rephrase and repeat questions to get a more complete or in-depth picture. It might be creating opportunities to observe customer behavior and activities. What works best will depend on the type of organization, the type of customer, and the type of product or service.

You might have opportunities for such activities now. Is there a recurring complaint you don’t know how to solve? Are you baffled by particular complaints? (Why would they complain about that?) These are opportunities to investigate meaning and expand knowledge about the voice of the customer. A understanding customers is crucial to success and growth.

WILLIAM LIMEN (verified owner) –

VERY USEFUL IN HELPING OUR COMPANY CREATE THIS MANUAL