Why ISO 22000?

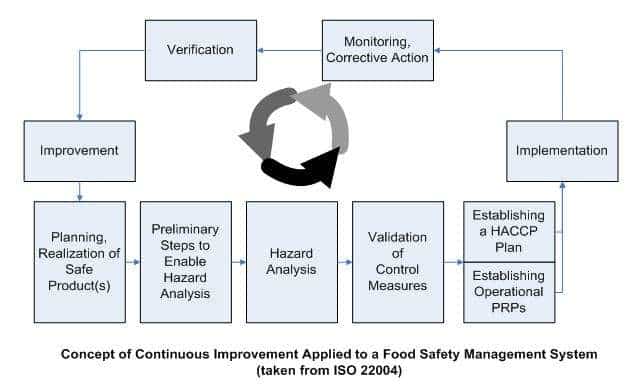

ISO 22000 will soon become synonymous with food safety. This ISO standard translates “food safety management” into a continuously improving process, designed to prevent or eliminate food safety hazards or, if they can’t be completely eliminated, at least bring them within acceptable levels.

Why Is There A Need For ISO 22000?

Recent surveys conducted by various testing and governing bodies (e.g., the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the USDA Economic Research Service) suggest that our food supplies are safer than ever. However, anecdotal evidence – stories many of us have seen or heard in the national and world news in recent days and months – strongly suggests to many consumers that it isn’t necessarily so.

Mad cow disease (bovine spongiform encephalopathy, or BSE) has caused countries such as Japan to ban the importing of beef. (BSE has been linked to a neurological disease in humans, known as Creutzfelt-Jakob variant.) Only after two years of rigorous, intensive testing and long negotiations between Japan and the U.S. did the Japanese market open up to American beef again.

Chronic wasting disease, which afflicts deer, elk, and moose in the wild, has become a concern for hunters and for state and federal conservation commissions. CWD, which is related to BSE, has not yet been linked to human illness but most states in the U.S. require testing of freshly harvested animals for CWD.

E coli (in Washington state (USA), raw milk was the source of infection of at least 18 people – Dec., 2005), salmonella (about 400 people in Ontario, Canada sickened by Salmonella, blamed on contaminated mung bean sprouts – Dec., 2005; fresh produce may be surpassing poultry as a cause of Salmonella, according to CSPI – Dec., 2005), and hepatitis A (lettuce served at restaurants in Los Angeles county (Calif., USA) – Dec., 2005) have been found far more than we would like in restaurants and supermarkets.

Can consumers ever be sure that the food they eat is 100% safe? If the public needs assurances that the world food supply is safe – and they tell us they do, repeatedly – where do we begin to look for answers?

The Food Supply Chain

The nature of food safety, just like the nature of the food chain, has changed over the years. Generations ago, people were very close to the source of food – in the 1860’s, 90% of the U.S. population was agrarian. People once raised crops and cattle for personal consumption and, when conditions permitted a bountiful harvest, sold their surplus directly to consumers at the farmers’ market in the nearest town.

“Food is our common ground, a universal experience.”

James Beard, 1903-1985

As the population increased and became more urbanized, a food supply chain came into being. Between the farmer and the consumer came companies that shipped, stored, and milled grain; bagged, stored, and shipped flour; mixed flour with other ingredients to make dough; baked bread and packaged it; and stored and shipped the bread to market.

Now, people bring their cuisines and their foods with them as they move across boundaries. Production around the world increases, so that many foods are no longer seasonal items. People are generally better informed about their choices and about food safety issues. With the increasing reach and complexity of the food supply chain, food safety becomes a more important issue than ever.

Safety Guidelines and Enforcement

Food safety rules and guidelines have existed for generations but have generally been developed and applied in a piecemeal manner. Many countries have their own food safety regulations and/or are using HACCP (Hazard Analysis & Critical Control Points); even within countries, there is little uniformity to food safety codes. For example, the United States has thousands of FDA laws pertaining to food safety and at least two departments – Agriculture and Health And Human Services – to enforce the rules.

Individual companies and food industry groups have also developed their own standards. Depending on the size and scope of a given company’s business, it may be responsible for knowing and applying the rules and standards of multiple countries and industries. The plethora of food safety schemes worldwide has led to uneven application of food safety standards, confusion regarding safety requirements, and increasing complexity and costs to suppliers that are obliged to conform to multiple programs.

What is Safe Food?

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) interprets “safe food” as food in which illness-causing substances (bacteria, chemicals, etc.), when they are present, are within acceptable levels. Through food research, the definition of “acceptable levels” is continually changing – for the better, it is hoped.

Through food research, the definition of “acceptable levels” is continually changing. Monitoring and measuring devices are hundreds – sometimes thousands – of times more precise than those of twenty, ten, or even five years ago. What used to be measured in parts per million (PPM) can now be easily and economically measured in parts per billion (PPB)! Levels of food safety hazards that might have been considered safe in the 1970’s or 1980’s may now be considered unfit for human consumption. We are also able to find things in our food that we didn’t know existed in food years ago, let alone were aware of their danger to our health.

Yet, even as we have become better informed individuals with regard to food safety, we have become more removed from the process of food production. For generations, people in developed (industrialized) countries have purchased their food from the supply chain, which has lengthened with each generation.

In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that the U.S. experiences between 4 and 7 million cases of food-borne illness annually, resulting in 5,000 deaths and costing the economy $3-6 billion in lost production, health care, and other expenses.

As the supply chain has lengthened, the risk of encountering food hazards – any biological, chemical, or physical agent that is reasonably likely to cause illness or injury in the absence of its control – has increased. Do we need more control?

What is Food Safety?

“Food safety” is about the prevention, elimination, or control of food-borne hazards at the point of consumption. Everywhere around the world, people agree on this one point –consumers need and deserve assurance that the food sold to them is safe to consume. As food safety hazards may be introduced at any stage of the food supply chain, every company in the supply chain must exercise adequate hazard controls. In fact, food safety can only be ensured through the combined efforts of all parties in the food chain.

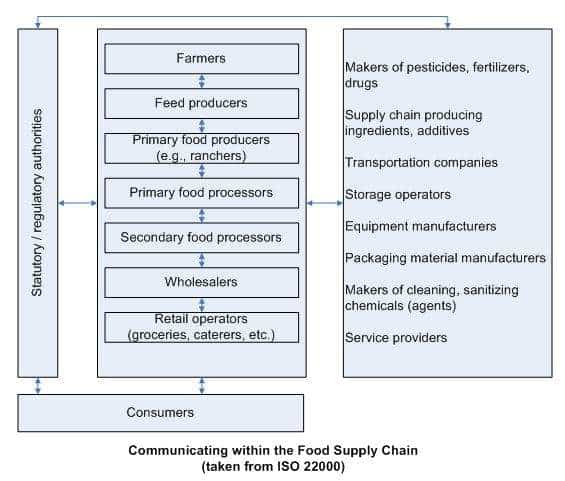

Organizations within the food supply chain range from primary producers (e.g., farmers, ranchers) through food processors, storage and transportation operators, subcontractors, and all the way to retail outlets (e.g., groceries, restaurants), as well as every point and company in between. And though their products are not part of the food we consume, makers of processing equipment, packaging material, cleaning agents, additives / ingredients, and even service providers (e.g., equipment testers) are also integral parts of the supply chain.

There are guidelines to follow, such as the BRC standard of 1996 and HACCP (a set of principles but not a true standard) but up to now, there has not been a single, internationally recognized food safety standard that applies to every link in the supply chain. That is, not until ISO registration to ISO 22000.

Hazard Access Critical Control Points – HACCP

This standard integrates the principles of the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point, or HACCP, system. It also incorporates application steps developed by the Codex Alimentarius Commission, a subgroup of the World Health Organization (WHO). Furthermore, ISO 22000 combines the HACCP plan with prerequisite programs, or PRPs.

Hazard analysis is the key to every effective Food Safety Management System – a hazard analysis helps the Company acquire and organize the knowledge needed to establish and implement effective hazard control measures. ISO 22000 requires that any hazard that may be reasonably expected to occur in the food chain is identified and evaluated, including hazards that could be associated with the type of process and the facilities used. Thus, the food safety standard provides the means for the Company to determine and document why it needs to control certain identified hazards and why other companies need not.

Critical Control Point (CCP)

A critical control point is a step in which control can be applied and is essential to prevent or eliminate a food safety hazard or reduce it to an acceptable level, or a point or procedure in a specific food system where loss of control may result in an unacceptable health risk. I think we all would agree that hazards are waste that must be eliminated from our food supply.

Food Supply Hazards

Examples of food supply hazards include:

- Disease or insects;

- Contamination, pesticides, or bioterrorism.

- Mishandling or improper preparation;

- Unsanitary conditions;

- Mislabeling or improper storage;

- Transportation (not inherently a hazard but the more ingredients have to be shipped over greater distances, the greater the chance of hazard);

- Multiple governing & inspection bodies (USDA, FDA, FSIS, CDC, EPA, USDHS, NAS, NCFST, BRC, IFST, FSANZ, FSAI, ad infinitum) with plenty of opportunity for conflict because of little-to-no coordination; and

- Lack of resources (money and people trained in food safety will always be in short supply).

Developing a HACCP Plan

Developing and following a HACCP plan makes good business sense and many governments now require that all companies in the food supply chain – from growers to sellers, and even equipment manufacturers – have their own HACCP plans.

Unfortunately, due to the varying nature of businesses in the supply chain, there has been no such thing as a HACCP plan – no uniform standard – that applied to all circumstances.

“If there is anything we are serious about,

it is neither religion nor learning, but food.”

Lin Yutang, My Country and My People

Furthermore, every nation, state, and locality has its own set of statutes and regulations governing food safety. Often, these laws are voluminous and cumbersome, and it is not unusual for food safety laws to overlap and even conflict. Up to now, there has not been a single, internationally recognized food safety standard that was applicable to every link in the supply chain and that worked in any setting, regardless of the local laws and customs. That is, not until ISO 22000.

Many governments felt a uniform set of procedures was needed; HACCP was one of the first attempts at a uniform set of guidelines. As good as HACCP is – many food companies have successfully implemented HACCP plans and many governments have passed regulations requiring food companies to develop their own HACCP plans – it isn’t uniformly applicable throughout the supply chain. That is, it lends itself better to some situations than to others. This is largely how the ISO 22000 standard came into being – governments and food companies wanted a standard to which everyone could be held.

While food safety is not guaranteed simply by virtue of a standard, with implementation and compliance with a standard like ISO 22000 throughout the food supply chain, consumers should have greater confidence in the safety and integrity of the food supply system and may be reasonably assured that the food they purchase is safe for them and their families to consume.

During hazard analysis, the Company determines the strategy and methods it will use to ensure hazard control by combining PreRequisite Programs (PRP), operational PRPs, and its HACCP plan(s).

The ISO 22000 Standard

ISO 22000:2005, “Food Safety Management System – Requirements for any organization in the supply chain”, is designed to provide a framework of internationally harmonized requirements for the global food industry. It allows every type of organization in the supply chain – from primary producers to food processors, to storage and transportation companies, to retail and food service outlets, and even makers of equipment used in food processing – to implement a Food Safety Management System, or FSMS.

In addition, food safety management systems that conform to ISO 22000 can be certified, unlike with HACCP. ISO 22000 incorporates the principles of HACCP and addresses the requirements of many key standards (such as the BRC, IFS, and EU have developed) in a single source document.

A huge plus of ISO 22000 is that it parallels the ISO 9001:2008 Quality Management System standard, which is already widely implemented in all types of industries. What this means to food companies looking to certify to ISO 22000 is that since the new standard is compatible with ISO 9001, firms that are already ISO-9001-certified should find ISO 22000 certification relatively easy.

While food safety is not guaranteed simply by having the ISO 22000 standard, with implementation and compliance throughout the food supply chain, consumers can feel more confident that the food they buy – regardless of where it came from or how it got there – is safe to eat.

To learn more about ISO 22000 download a free procedure sample today.

ISO 22000 Design

ISO 22000:2005 is designed to ensure that the food supply chain has no weak links. It does this by specifying the requirements for a Food Safety Management System (FSMS) that combines the following generally recognized key elements to ensure food safety up to the point of the consumer:

- Interactive communication;

- System management;

- Prerequisite programs; and

- HACCP principles.

Effective communication – up and down the food supply chain – is critical to the control of food safety hazards. Communication between the Company and its suppliers – as well as between the Company and its immediate customers – helps ensure that all relevant food safety hazards are identified and are adequately controlled at each step in the supply chain. Communicating with the Company’s customers and suppliers about known hazards and how to control them also helps to clarify customer and supplier requirements. All parties need to know the feasibility of and need for these requirements, as well as what their impact on the end product might be.

Understanding the Company’s role and position within the food chain is an essential part of ensuring effective interactive communication throughout the chain. A simplified illustration of communication channels among members of the food supply chain is shown on the next page.

The most effective food safety system is established, operated, and updated within the framework of a structured management system and is incorporated into the Company’s overall management activities, such as strategic planning. This will provide maximum benefit not just to the Company, but also to its suppliers and customers.

ISO 22000 has been aligned with ISO 9001 to enhance the compatibility of the two standards. Though there is naturally much commonality between the two international standards – the quality standard being a parent of the food safety standard – ISO 22000 can be applied independently of ISO 9001 or any other management system standard. The Company can align (integrate) its implementation of ISO 22000 with existing related management system requirements, or it may utilize existing management systems to establish a food safety management system that complies with ISO 22000 requirements.

An Auditable Standard

ISO 22000 was designed to be an auditable standard; by way of comparison, HACCP plans are based on the seven HACCP principles. There are guidelines and models the Company can use to develop its HACCP plans, but there is no auditable HACCP standard. It is not practical to require companies to have identical HACCP plans; in fact, any Company may need several HACCP plans, one for each product line.

One of the reasons ISO 22000 was developed as an auditable standard was to facilitate its application over the entire length of the food supply chain. The standard applies equally well to food growers, food retailers, and every step in between. Individual organizations are free to choose the necessary methods and approaches to fulfill ISO 22000 requirements, however. Companies implementing the standard should find improvements in their food safety management systems over time, regardless of whether they’re certified. (To help the Company implement this standard, guidance on its use is provided in ISO/TS 22004.)

Note that ISO 22000 is intended to address food safety concerns only. The same approach provided by this standard may be applied to other food-related issues (e.g., ethical issues, consumer awareness).

Also noteworthy is the fact that ISO 22000 does allow smaller and less-developed companies to implement externally developed control measures.

The aim of the developers of ISO 22000 was to harmonize requirements for food safety management for businesses within the food chain on a global level. The standard is particularly aimed at organizations that seek a more focused, coherent, and integrated food safety management system than the law typically requires. It requires an organization to meet any applicable food safety related statutory and regulatory requirements through its food safety management system.

Copies of the ISO Standard

A copy of the standard, “ISO/FDIS 22000:2005 – Food Safety Management Systems-Requirements for any Organization in the Food Chain”, is available for a small charge[1] from ISO (http://www.iso.org). You can have it shipped to you in hardcopy form or you can download it from the ISO web site in “.pdf” format.

Certifying to the ISO 22000 Standard

BVQI was the first organization to certify a food safety management system to the ISO 22000:2005 standard; it certified a Danesco Sugar plant in late December of 2005. NSF International (http://www.nsf.org) is another organization that is capable of certifying food safety management systems. Contact ISO (http://www.iso.org) for the certifying body nearest your location.

The International Register of Certificated Auditors (IRCA – http://www.irca.org) is one organization qualified to train and certify food safety auditors. Other such organizations may be found by visiting the ISO web site.

Very informative content. I was not having knowledge of ISO 22000. Thanks for explaining ISO 22000 in very simple manner. It was worth reading.