How Do You Fix Bad Business Policies?

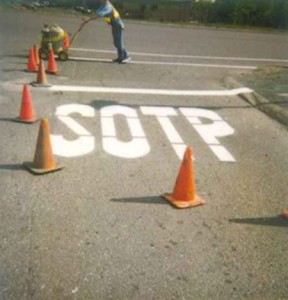

Some business policies are the result of undesirable consequences or something happens that shouldn’t. For example, a door isn’t secure from the outside and someone gets in your building who doesn’t belong. Now management creates a policy restricting the door’s use. For example, “That door is for exiting the building ONLY in case of emergencies. It is NEVER to be used as an entry.” Should we be enacting bad business policies or fixing the door? How do you fix bad business policies?

What are Bad Business Policies?

Some — such as high-level, or corporation-wide — business policies are designed to promote desirable consequences for an organization, as well as prevent undesired ones. Bad business policies cannot be corrected by procedures, no matter how well the procedures are written.

Bad Policy Example

The Glass-Steagall Act (aka, the Banking Act of 1933 – USA) was enacted in response to the massive failure of commercial banks in the early thirties. Commercial and investment banking, among others, were separated in an attempt to minimize risk.

This risk-averse policy appeared to work for the economy in general, though it didn’t work for large investors and institutions that wanted to “compete with overseas institutions that (were)n’t hamstrung by archaic laws”. Totally ignoring the issue of increased risk, banking and investment moguls pushed for a law like Gramm-Leach-Bliley…and they got it.

They (Citibank, Bear Stearns, etc.) managed to undo Depression-era restrictions on consolidating and diversifying, and they grew dozens of times over. That is, until their hubris caught up with them and the “Great Recession” exploded onto the economic scene. Derivatives processes — they failed in part because they were overly complex; they also failed because of the economic policies that allowed them to exist.

So, how do we fix bad business policies ?

Correcting Bad Business Policies

Undesirable business policies are best solved by taking corrective action and eliminating the bad policy. And how do we take corrective action? Or, to put it another way, how do we go about eliminating bad business policies?

1. Describe the Policy Problem

Describe the bad business policy problem in clear, concise language. Get several views of the problem — no one sees everything and everyone sees the same thing differently.

2. Find the Policy’s Root Cause

Once you’ve begun to understand the policy problem, delve into it further by looking for its root cause. A commonly used tool for discovering root cause (because it’s simple, effective, and time-tested) is “5Y”, or “the five whys'”.

Five Whys (5Y)

You know how children wear you down by continually asking you “Why?” (“Why?…Why?…Why?…Why?…”) That’s sort of how you use “5Y” — you keep asking “Why?” until you’ve found the root cause of the problem. It’s called “the five whys” because nearly all root causes are identified by the fifth “why”.

By then, it should be obvious that a one-time “quick fix” won’t solve the problem. The bigger challenge is how to keep the problem from recurring.

Developing Business Policies

Well, that’s where developing business policies comes in. It’s a high-level look at the situation. What are we going to do (or not do), what do we want to achieve (or avoid), and, most of all, why?

What happens when you tell your child, your spouse, or your coworker, “Just do it!” First thing out of their mouths, of course, is “Why?”, as in, “Why should I do it?”

It’s a reasonable question, so why not answer the question before they ask? Doing so at the outset will save you countless (and sometimes massive) headaches. When you get buy-in from stakeholders, your compliance rate goes way up.

3. Summarize Policy Actions

A policy merely summarizes the corrective action system. You might call it the “cornerstone” of a corrective action system. The corrective action itself is the heart of the system, a system that follows the “Plan-Do-Check-Act” model:

- PLAN the corrective action;

- DO, or implement the action and collect data;

- CHECK the corrective action – see if the data prove that the corrective action is effective or not and if not, change what doesn’t work…or make changes because “good” isn’t “good enough”; and

- ACT – continue with the system unchanged, because it’s yielding the desired results, or implement the revised system.

In case you didn’t notice…document that corrective action process and – voila – there’s your procedure!

4. Identify Policy Roles and Responsibilities

Identify roles and responsibilities with respect to the business policy. Don’t just say “the company” or “we” (unless, of course, you’re dealing with a high-level policy). The last thing you want to hear is, “I thought you were going to do it!”

5. Develop a Draft Policy

Once you’ve developed a business policy draft, have a reasonable number of stakeholders review it. You might think those who are responsible for carrying out the policy and enforcing it have the greatest stake…and you’d be right, but you can’t overlook the other employees, including management.

No one’s working in a vacuum. For instance, let’s say you’re working on a purchasing policy. Give them time to make comments but make the end of the comment period absolute. You can always change it – nothing, not even policy, is set in stone. Focus on continuous improvement, not delayed perfection, especially if it takes forever getting a policy “perfect”.

6. Review and Revise the Policy

Revise the business policy as needed and get Management’s approval – which should be easy, since you’ve had them involved in the policy-making process. (You did get them involved, didn’t you?)

7. Distribute the New Business Policy

Not part of the development process, per se, but its logical conclusion: Distribute the policy, instruct your employees on it, and put it into practice. Do, check, and act.

You may have noticed that each of our free policies and procedures has a policy statement. Those are purposely vague because we don’t know our customers’ exact situations, requirements, or objectives.

As we often say, “We’ve laid the foundation — you build on that.” Obviously, your policy statements can’t be vague. Your employees need to know exactly what to do and why.

Do You Fix Bad Business Policies?

employment policies

To quickly sum, you need to identify the problem, figure out what caused it, develop a system to prevent the problem from recurring (or lessen its likelihood) and enact it, and summarize that system in a policy statement. And don’t forget — you need to review your policies regularly to ensure that they reflect the current and future state of your business, not what used to be done in the past. Then, If you decide you need to make a change, figure out whether or not it’s time for a policy revision, training or additional resources.

Download Sample Policies and Procedures Templates

Review free policies and procedures to see how easy and fast it is to customize the MS-Word templates for your business. No other company provides a complete set for your whole company. More questions? Learn how to improve your organization by using policy management software.

Interested in Sample Polices and Procedures Templates.

Samples are available at https://www.bizmanualz.com/sample-policies-procedures